The recipe of the month is for French Galette Complète, a savory form of crêpe from the Brittany region. The crêpe itself has only 3 ingredients (buckwheat flour, water and salt) but is adorned with ham, cheese and a soft-cooked egg.

The French Crêpe (pronounced “krep”) is known around the world and has a huge number of variations. The circumflex above the initial “e” in the word orthographically denotes that previously the letter “s” followed the “e”, so presumably the original spelling was crespe. The word crêpe is derived from the Latin work crispa meaning either curly, wrinkled or crinkled, and those sorts of qualities are shared by crepe paper and crepe fabric.

Crêpes are, of course, quintessentially French (although many countries have their own versions). They are most often eaten for lunch or dinner (less so for breakfast!), and it is not rare that someone might enjoy a savory crêpe for a main course and follow that with a crêpe sucre (sugar crêpe) for dessert. One poll of Parisians found that of the many varieties of crêpes, the basic crêpe sucre was the most popular. February 2nd is the Catholic holiday of Candlemas, and it is also known as jour des crêpes (day of crêpes) as on that day crêpes, which are considered to symbolize prosperity, are enjoyed throughout the nation.

It is generally believed that the French crêpe had its origins in Brittany and certainly that area of France has a higher number of “crêperies” (shops, stands or restaurants that specialize in crêpes) than anywhere else. However, the type of crêpe that is most common in Brittany is not the white, wheat kind that most people outside of France are familiar with. Known as Galette Bretonne, these crêpes are made of buckwheat. And the most popular type found there is the Galette Complète, which are savory, not sweet. Therefore, it is possible that the very first crêpes in France were made of buckwheat flour, not wheat flour. Brittany is also famous for its apples and as many as 200 varieties are grown there. Not surprisingly, the most popular accompaniment for a Galette Bretonne is very dry (brut) sparkling cider, served in wide-mouth cups known as bolées, a.k.a “cider bowls”.

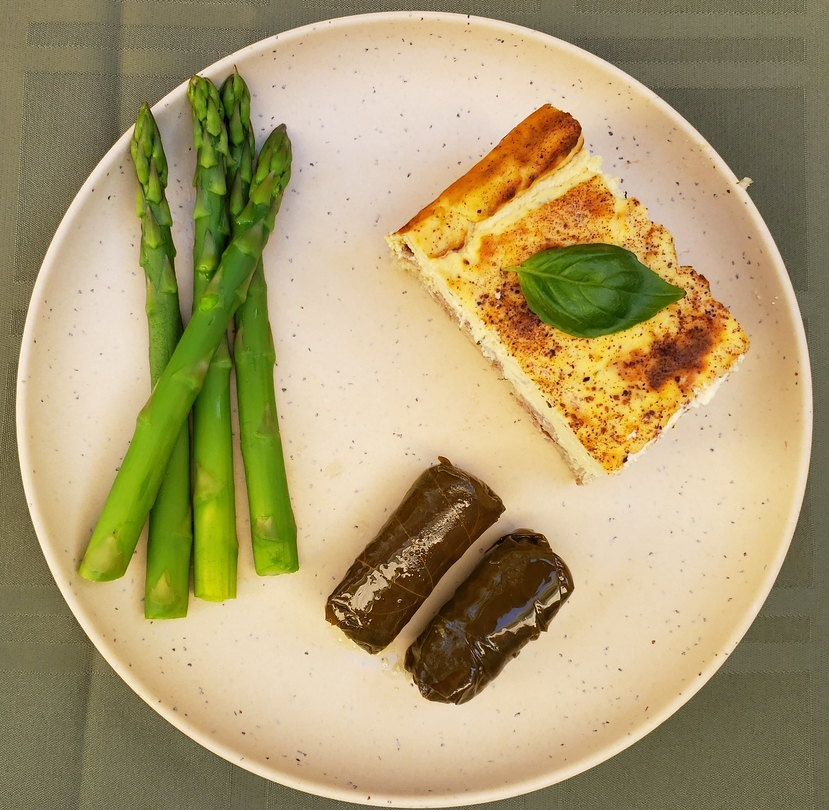

“Galette” is the French word that refers to a small round cake. There are many types--not all are paper thin. Although galettes are often make of buckwheat, there are also potato galettes (galette pomme de terre). Many types of galette share a common feature with Galette Bretonne, the edges of the pastry are folded inward, partially covering whatever filling is used. Often these other kinds of galettes are round in shape, but in the case of Galette Bretonne: a square shape is created by making four equal folds of the round crêpe.

The biggest difference between crêpes and pancakes is that crêpes don’t have any leavening agents like yeast or baking powder, so they don’t rise when cooked. They should be thin and flat. Additionally, crêpes typically include eggs in the batter and sometimes use milk instead of water. Whatever you decide on, the most important consideration is that the batter, unlike pancake batter, should be very thin, about the thickness of heavy cream. The problem that has confronted many chefs and cooks with preparing traditional Galette Bretonne is having the buckwheat crêpe crack and crumble during folding. The solutions these cooks have arrived at is to add either eggs or wheat flour to the batter. This is not traditional and there may be a better solution: cooking the crêpe at a higher temperature so that it crisps up (and unlike wheat crêpes, they should be slightly crispy) before it dries out. As always, experiment and find out what works best for you.

Making your own crêpes is a lot easier if you have the proper equipment. In France most households have a carbon-steel or non-stick flat pan more or less a foot wide with a shallow edge. Using one of these pans, you have to develop the technique of tilting and rotating the pan quickly to evenly distribute the batter. Some are made of cast-iron, presumably not for people with weaker wrists! If you wish to old-school-it, knock yourself out. Enter the “billig” or crêpe-making machine. Modeled on professional crêpe-makers used by restaurants, consumer-level crêpe-makers are inexpensive and highly versatile. They are flat, round, non-stick cooking plates with enclosed electric coils beneath and the temperature is adjustable. We love ours and have used it for making fajitas, pancakes, parathes, and omelets. Apparently they can even fry bacon, but we haven’t tried! Ours heats very evenly. Such machines run from around $30 - $40 (although much more expensive ones can be found). We have a Proctor-Silex one, which seems to be a bit sturdier than the cheaper Nutra-chef one that we found was not airline baggage-handler proof. Typically, these machines come with “spreaders” – T-shaped utensils for spreading the batter and a long thin spatula useful for folding crêpes and removing them from the pan. Using the spreader requires a level of skill I have not yet mastered. So ever open to experimentation, I donned a pair of thick oven gloves, lifted the entire crêpe making machine, tilting and swirling until I created a round thin crêpe. Worked like a charm, but do this at your own risk, and I wouldn't attempt it with anything other than thick oven gloves!

Galette Complète are topped with ham, cheese and a single whole egg. Recipes vary on preparation. Perhaps the most traditional method is to add the toppings on the crêpe while it heats up. Other recipes call for making a stack of crêpes, each browned on both sides and then re-heated with the ham, cheese and egg on top. Other recipes call for cooking the egg separately and adding it before folding in the sides. America’s Test Kitchen, no fans of tradition, suggest baking everything in an oven! But perhaps the oldest method is to add the batter to the pan, sprinkle a circle of cheese half way from the center (creating, as one recipe observed, a wall to prevent the egg from spreading too far), add pieces of ham on top of the cheese and then cracking an egg in the center. Some cooks use a spoon to spread the egg white over the cheese. I’m not sure what that achieves; there should be no disadvantage to simply waiting until the egg white is fully cooked. The only problem I encountered was not making a sufficient wall with the cheese which let the egg white run off the crêpe, but leveling the machine and adding more cheese in subsequent attempts solved this problem. After some experimentation I found cooking one side of the crêpe, flipping it over and then adding the toppings seemed to work best.

Most recipes call for the use of Swiss Emmental cheese, but others suggest using French Comte which is for all intents and purposes the same as Swiss Gruyère. However, this might not be as cut and dry as it may seem, because in Comte they also make Emmental Français! Confused? Don’t worry, according the Paroles de Fromages (the Cheese School of Paris), “the difference between the Gruyere and the Emmental is above all a question of holes. Those in the Emmental are bigger!”

Cook’s notes:

Whenever a recipe calls for an egg with an unbroken yolk, it’s a good idea to break the egg into a cup or a bowl first and then into the dish you are preparing. It’s more likely that the yolk will break when you crack the egg, than when transferring an unbroken egg from a bowl to a dish. This way if you break the yoke you can try again without ruining the dish!

The New York Times recipe for Galette Complète calls for “Jambon de Paris (or other ham)”. Paris ham is difficult to find and very expensive. Jambon de Paris is unsmoked shank portion ham that is cooked in a stock of a stock made of juniper, coriander, cloves and a bouquet garni. One day I might try making my own! A good substitute would be unsmoked deli ham. If you are buying a whole or half ham, get a “city ham” rather than a generously salted “country ham”. One might be tempted to buy an “uncured ham”, but this is more marketing than science (and poorly regulated by the FDA). Unfortunately, “natural uncured” deli or prepackaged ham have just as many nitrites as hams that are not marketed as such, even though the nitrites are from “natural sources” (like celery juice). 1

The first and last crêpe are unlikely to be a success: the first due to mysterious forces no one really understands and the last one because it is likely there is not enough batter. In France there is a saying “La crêpe du chat” meaning “the cat’s crepe” indicating something that is so ugly it’s only fit for a cat! Nearly all recipes boldly state that the batter should be “rested” for anywhere from 30 minutes to a full day, on the belief that the resulting crêpe will be “lighter”. However, Daniel Gritzer a writer for Serious Eats claims as buckwheat flour has no gluten (resting allows gluten chains to connect), there is no good reason to rest the batter. I tried both ways and also found little difference in the result.

1 Is celery juice a viable alternative to nitrites in cured meats? McGill University’s Office for Science and Society.

Ingredients (for 4 servings):

For the batter:

- 1 Cup buckwheat flour (they have this at Sprouts)

- 1 Cup of water

For the filling:

- 4 Large whole eggs

- 4 Ounces of grated Emmental, Compte or Gruyère Cheese

- 6 Ounces of thinly sliced jambon de Paris or other “city ham” (see notes above)

- Several sprigs of finely chopped Italian parsley (optional)

- Salt and Pepper to taste

Preparation:

- Take the eggs out of the refrigerator and let them reach room temperature (no more than 1 hour).

- Whisk ½ cup of the water into the buckwheat flour.

- Keep whisking and adding water until the batter is very thin, approximating heavy cream in thickness.

- Let the batter rest for ½ hour (optional, see note above).

- Heat the crepe machine up for at least 10 minutes to a temperature of 375 ° (6 1/2 on our machine).

- Pour 1/2 cup of batter onto the crepe machine and using the spreader (or the hack mentioned above) in a circular motion spread the batter into a large round shape.

- When the batter turns dull (no longer shiny, should take about a minute at 375°) flip the crêpe over.

- Create a circle of grated cheese with one ounce of the cheese half way from the center of the crêpe.

- Carefully crack an egg into a bowl or cup and then slide the whole egg onto the center of the crêpe that is cooking.

- Tear or festoon the pieces of the sliced ham and festoon them around the egg yolk.

- Continue cooking the crêpe until the whites of the egg are fully cooked. Please note that this will take some time. But fear not because at 300 – 400 ° the crêpe is very unlikely to burn. Indeed, I purposely cooked a crêpe for 12 minutes at this temperature and it didn’t burn at all.

- Salt and pepper to taste.

- Fold the edges of the crêpe over the cheese and ham (but don’t cover the egg yolk) to create a square (see photo).

- Lightly garnish with chopped Italian parsley (optional).

- Serve with a “bowl” of extra-dry (brute) sparkling alcoholic cider.

Bon Appétit!

Recipe by T. Johnston-O’Neill

Photos by Shari K. Johnston-O’Neill