Mexican Pozole Rojo , or red pozole, a fiery corn-based dish that tantalizes the taste buds and warms the body. There is a considerable amount of preparation involved, so pozole is considered a special treat made for birthdays, Independence Day, Christmas and other holidays. Pozole has its origins in pre-Columbian traditions. As detailed in the Florentine Codex*, Aztecs and other Mesoamericans perceived maize as a sacred plant connected to humanity's origin. According to lore, the gods formed human beings out of masa, thus linking it to the basis of life itself. According to the Florentine Codex after ritual sacrifice, a common religious practice for the ancient Aztecs, the body would be broken down, cooked into pozole and consumed by the community as an act of religious communion. Presumably, after the Spanish outlawed cannibalism in Mesoamerica, alternatives were explored, leading to new recipes with chicken and pork. While the origin is fascinating, I for one am glad I get to enjoy this delicious soup in its modern iteration.

>The Spanish term pozole comes from the Nahuatl word for hominy, an ingredient that sits at the center of Mexican cuisine. The alkali-treated corn kernels are the basis for masa harina, the corn flour that is used to make tortillas and tamales. The treating process, known as nixtamalization, allows necessary nutrients like niacin and calcium to be absorbed by the human body.

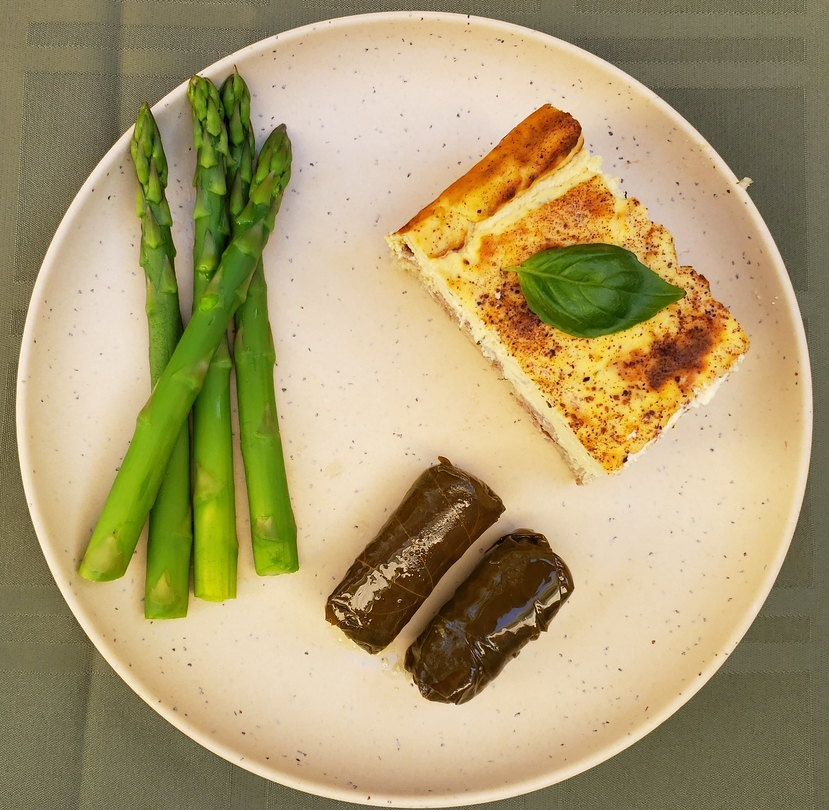

In addition to hominy, pozole typically contains pork (though other meats are also used) and various chilies, and is accompanied by a multitude of garnishes. Shredded green cabbage, diced onion, tostadas, avocado, cilantro, oregano, radish and lime really round out the flavors in the bowl.

Three types of pozole are common: red, white and green. All three of these are riffs on the simple concept of hominy and broth. Red pozole takes its color and flavor from dried red chilies like ancho and guajillo, which are softened and then ground into a paste. Green pozole uses ingredients like tomatillos, epazote, fresh green chilies, cilantro and pepitas to form a rich and fresh soup. White pozole is the most traditional preparation as it forgoes the red or green ingredients in favor of hearty simplicity.

The following recipe is a variation on the classic red pozole. Traditionally, a bone-in piece of meat would be boiled with aromatics to produce a broth. I instead roast boneless pork shoulder and make a simple pork stock separately. This produces tender pork and a rich, flavorful stock. Feel free to use whichever method suits your personal preference. Most, if not all, ingredients can be found at a Mexican or Latin American grocery store such as Northgate Market or Pancho Villa Supermarket.

Cook's note: Like most recipes that call for marinating meats, the initial preparation for this dish is best done a day before. At the very least the meat should be marinated for an hour, but 12 to 24 hours is better.

*Editor's notes: The Florentine Codex is the best preserved part of a larger 12 volume codex now known as the "Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva Espa&ntilda;a" (The General History of the Things of New Spain). Originally published in 1569, the text is known as the Florentine Codex because it is held in Medicea Laurenziana Library in Florence, Italy

The compiler of the work was Bernardino de Sahagún, a Jesuit priest and early ethnographer who learned Nahuatl and spent more than 50 years studying Aztec beliefs, culture and history. Sahagún, whose primary goal was to convert indigenous people to Catholicism, held rather strong opinions on Aztec cultural practices and beliefs, greatly admiring some while despising others. It should be noted that considerable research and scholarly writing has challenged many post-contact reports regarding the extent of cannibalism, so the veracity of Sahagún's (who again was most interested in converting Aztecs to Catholocism) references to cannibalism among Aztecs, remains in question. His scholarly method, however, was pioneeringly ethnographic.

The text of the Florentine Codex is bilingual with Spanish on the left-hand side of each page phonetically transcribing Nahuatl, which is written using Latin letters on the right. The illustrations and much of the text were created by Aztec students, village elders and artists. The entire Florentine Codex has been digitally scanned in high resolution and can be found here. The quality of the scan is exquisite and digitally leafing through the pages is beyond thrilling—even if you don't read Spanish or Nahuatl.

Ingredients:

Chile paste:

- 4 Ancho chilies, seeded and stemmed

- 4 Guajillo chilies seeded and stemmed

- 4 Árbol chilies, seeded and stemmed

- Water to cover

Pork broth:

- 2 pigs feet, halved (ask your butcher to do this)

- 1 pound pork neck bones

- 1/2 medium onion

- 1 small head of garlic

- 3 bay leaves, dried

- 1 teaspoon black peppercorns, toasted

- 2 teaspoons smoked paprika

- 2 teaspoons Mexican oregano

- 2 tablespoons kosher salt

Roast pork:

- 1 1/2 pounds pork shoulder, deboned or boneless

- 1 tablespoon Kosher salt

- 1 tablespoon Achiote powder

- 4 garlic cloves, minced

- 8 ounces fresh orange juice

- 4 ounces fresh lime juice

Finishing and serving:

- 15 ounces can-prepared hominy

- Tostadas

- Avocado, sliced

- White onion, diced

- Radishes, thinly sliced

- Green cabbage, shredded

- Cilantro, chopped

- Lime wedges

Preparation:

- The day before cooking, combine fruit juices, garlic, salt and achiote in a bowl, mixing thoroughly.

- Place the pork shoulder into a gallon-sized bag and add the marinade. Let the mixture sit overnight in the refrigerator, turning once.

- The next day, remove the pork from the refrigerator and let it sit at room temperature for 1 hour.

- Forty-five minutes after the pork is removed from the refrigerator, preheat the oven to 300 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Place the pork on a wire rack over a sheet tray and roast in the oven for 4 hours or until pork is very tender.

- Remove from the oven and let rest for about 30 minutes before shredding.

- Heat a small skillet over medium-low heat until warm and then add the chilies.

- Toast the chilies, turning frequently, until fragrant and beginning to blister in places: approximately 2 minutes for the Árbol chilies and 4-5 for the Ancho and Guajillo.

- Transfer the chilies to a small saucepan and cover with water. Bring the pot to a boil and cook the chilies for 3 minutes.

- Add the chilies, their boiling liquid and 1 teaspoon of kosher salt to a blender and blend until smooth. A thick red paste should form.

- In a large heavy bottom stock pot or Dutch oven, place the pork bones and feet. Cover with cold water and bring to a boil.

- Once boiling, cut the heat, drain and thoroughly wash the bones in running water. Rinse the pot of any sediment or residue.

- Return the cleaned pork bones and feet to the pot. Add the onion, garlic, paprika, peppercorns, bay leaves, salt and oregano and enough water to cover.

- Bring the pot to a rolling boil and skim any foam that forms on the surface. Boil for 15-20 minutes and then lower the heat to a bare simmer and cover the pot.

- Simmer the mixture for another 2 to 3 hours, adding water as necessary to keep the bones covered.

- Once the liquid has become infused with the spices and the pork has a lightly velvety mouthfeel, strain the broth through a fine mesh sieve, discarding the solids.

- Add all of the broth back into the stock pot or Dutch oven along with about 3/4 of a cup of the chilie paste and the drained hominy.

- Bring the mixture to a boil over medium high heat and cook until the hominy is hot and the broth has thickened slightly (about 20 minutes).

- Add the pork and continue to cook until warmed through and thoroughly coated with the soup.

- Serve the soup in bowls with garnishes on the side or piled on top.

Recipe and Photo by Liam Fox

Notes on Codices by T. Johnston-O'Neill